Case Study

From Global to Local – Building Resilient UNESCO Networks in the UK

Liam Smyth, Programme Lead at the UK National

Commission for UNESCO

Background

Over the past decade, the UK’s relationship with UNESCO has been marked by both uncertainty and opportunity. At one point, between 2016 and 2018, the UK even considered withdrawing from UNESCO, raising urgent questions about how to demonstrate the value these sites bring to the public, despite the UK’s rich portfolio of World Heritage Sites, Global Geoparks, Biosphere Reserves, and Creative Cities.

Yet the potential of these designations was clear. By definition, UNESCO sites are world-class destinations – places where culture, nature, and heritage converge, often right on people’s doorsteps. Their value lies not only in their international recognition but in their ability to foster shared ownership, inclusion, and pride among local communities.

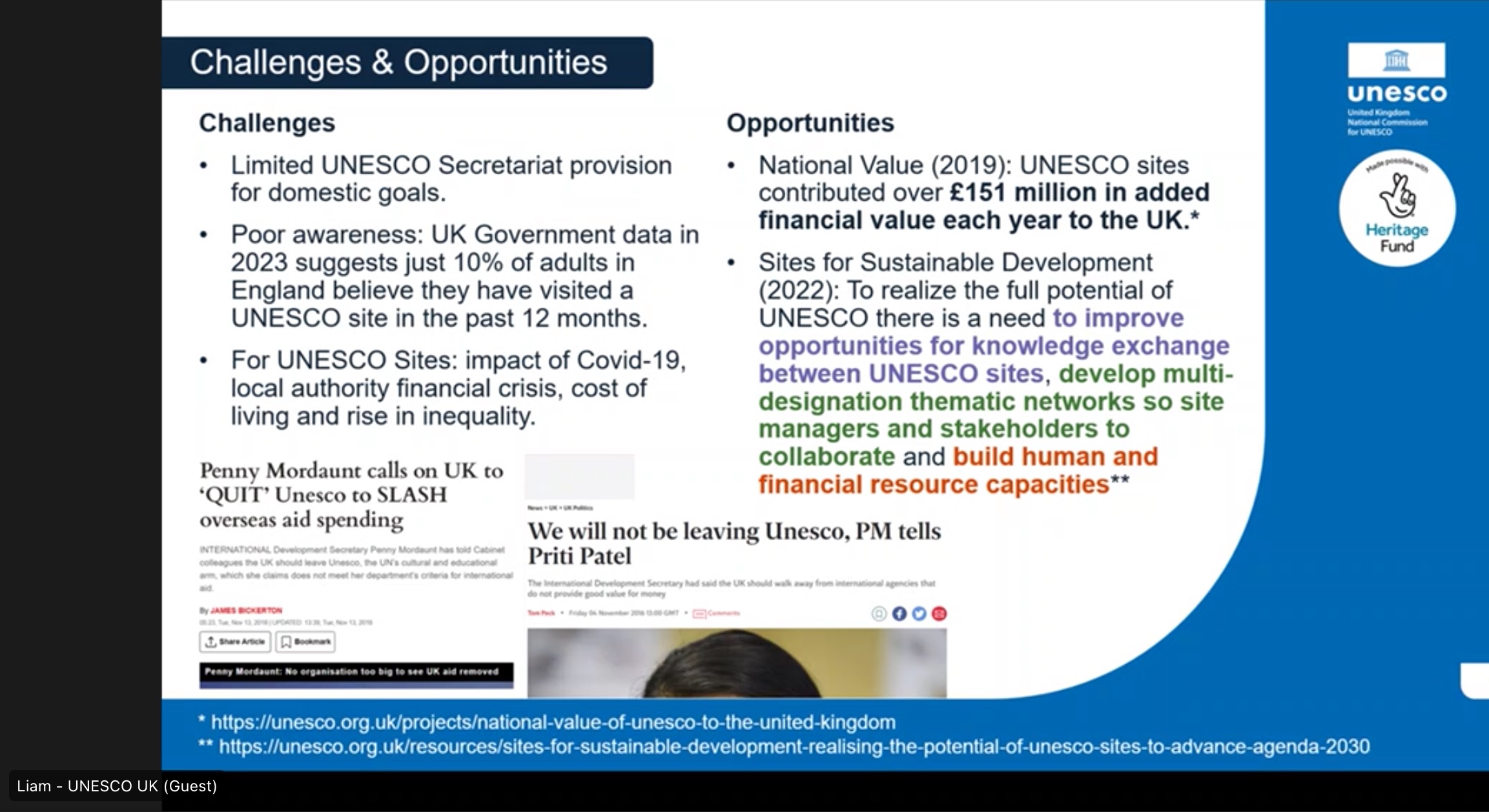

The challenge was that this value was not being fully recognised. Public awareness remained low: surveys consistently showed that only around 10% of adults in England believed they had visited a UNESCO site in the past year, despite millions of actual visits. Support structures were limited too, with the UK National Commission for UNESCO reporting directly to the Foreign Office – an arrangement that streamlined international policy advice but left domestic engagement underdeveloped. Add to this a volatile global context – from climate change to political and economic instability – and it was clear that the UK’s UNESCO network needed a new model to thrive.

Faced with these challenges, the UK’s UNESCO community needed a new way to work: one that stretched resources further, built resilience, and demonstrated tangible value.

Three main challenges stood:

- Limited domestic support: As the UK National Commission for UNESCO reports directly to the Foreign Office, there was little provision for public-facing awareness or engagement.

- Low public recognition: Government surveys showed that only 10% of adults in England believed they had visited a UNESCO site in the past year – despite millions of visits annually. Visitors simply didn’t realise the global significance of the places they enjoyed.

- Volatility and uncertainty: UNESCO sites were increasingly exposed to wider crises – climate change, economic instability, political shifts – yet had limited resources to respond.

Approaches

The From Global to Local programme was designed as a model, way to strengthen collaboration, stretch resources further, and ensure that UNESCO sites in the UK could act not as isolated designations, but as a powerful, interconnected network capable of inspiring local action and contributing to global goals.

The vision was clear: “By connecting local heritage to global goals, Local to Global demonstrates the power of UNESCO sites to inspire change, test new approaches, and amplify their impact.”

The From Global to Local programme set out to:

- Build a more resilient and adaptable network of UNESCO sites across the UK.

- Strengthen collaboration between very different types of designations – from natural landscapes to creative hubs.

- Create opportunities for shared knowledge, skills, and resources.

- Position UK sites not just as local treasures, but as part of a global network with global goals.

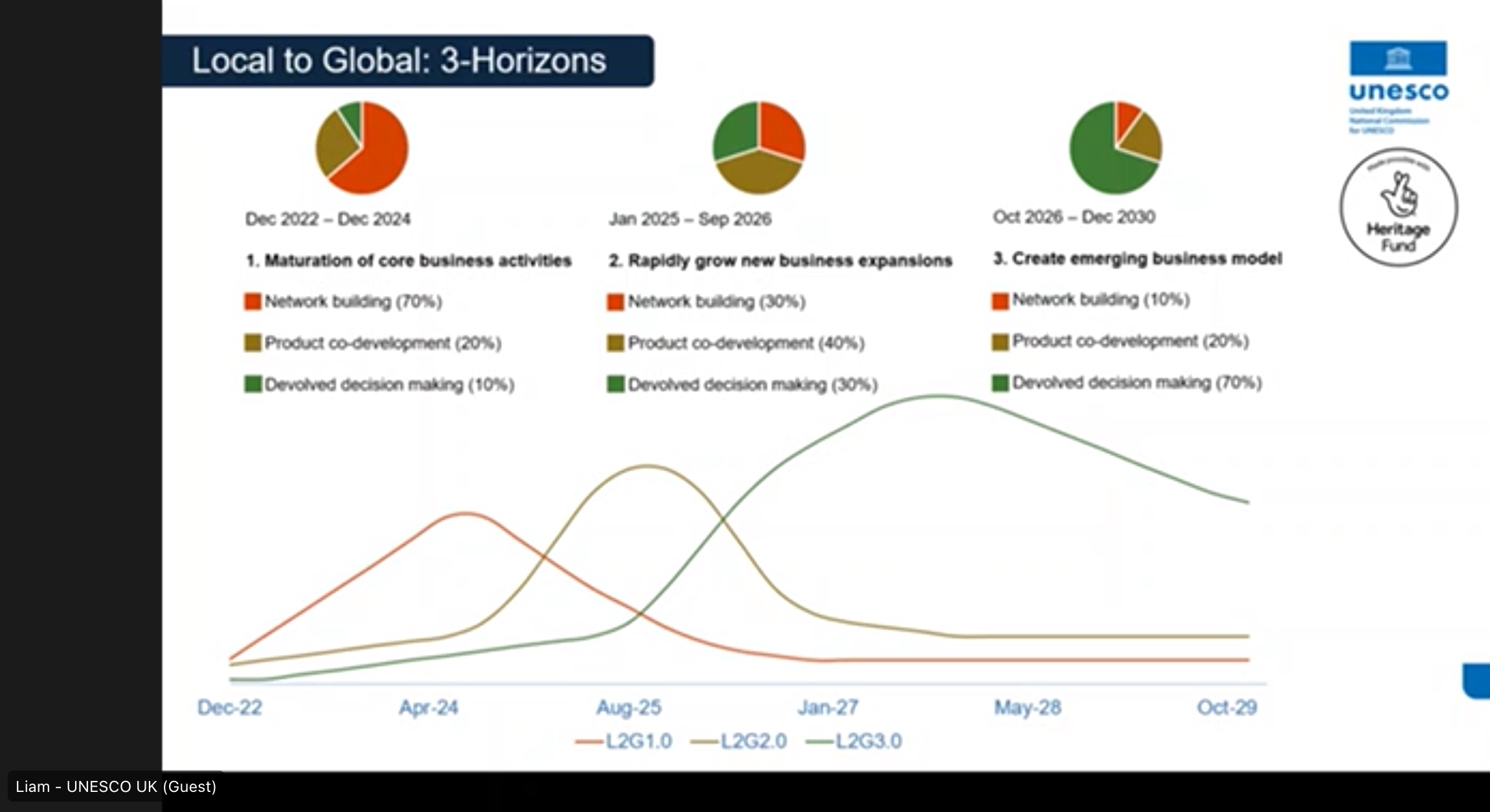

The UK National Commission adopted a three-horizon change model.

Resources

Rethinking Heritage Futures, Online Workshop “Developing International Collaborations and Creative Partnerships”, 24 June 2025, Nottingham Trent University (NTU), Communication University of China (CUC).

Approches

1. Horizon One – Building Trust and Networks

At the start, the emphasis was on building trust and connections among sites that had often worked in isolation. Workshops, held both online and in person, brought together managers from across the UK to share experiences and begin shaping a common agenda. These encounters were not always easy. Differing perspectives sometimes clashed, and the instinct at first was to avoid conflict in order to keep conversations smooth. But it quickly became clear that disagreement was not a weakness – it was an inevitable part of collaboration. By embracing conflict management and introducing more deliberative democratic processes, the network found a way to turn difference into strength.

This approach came to life most vividly during a series of six horizon-scanning workshops. Sites across the UK gathered to map their resilience thresholds, identifying where pressures were greatest and where opportunities might lie. The process not only engaged every single site in the network – a rare achievement – but also revealed three shared priorities that cut across designations: audience development and inclusion, financial sustainability, and digital transformation. For the first time, World Heritage Sites, Biosphere Reserves, Creative Cities and Geoparks could see that, despite their differences, they faced common challenges and could learn from one another.

2. Horizon Two – Expanding and Sharing Resources

With this foundation of trust and shared purpose, the network moved into its second phase: creating new tools and resources together. Out of co-design emerged a digital map and resource hub, designed not in isolation but shaped collectively by the sites themselves. What followed was an exercise in the power of networks. With little funding for paid promotion, the team relied on the advocacy of individual sites, who shared the map with their devoted online audiences. The result was extraordinary: web traffic rose by 400% at launch, with two-thirds of that growth coming organically through the enthusiasm of the network.

Early examples included:

- Film projects showcasing multiple UNESCO sites in a region.

- Regional fundraising feasibility studies that attracted private sector partners like railway companies.

- Creative crossovers such as artist residencies in natural heritage sites, bridging urban Creative Cities and rural reserves.

3. Horizon Three – Towards Devolved Decision-Making (in progress)

As the network matured, the third horizon began to come into focus. The aim now is to shift more decision-making from the top down to the bottom up, empowering sites themselves to lead strategy and innovation. Early signs of this are already visible. Regional collaborations are generating new political support, while UK sites are positioning themselves as testbeds for major innovation projects – such as the £1.8 million UNESCO Climate Change Heritage initiative. The ambition is that in the future, the network will not simply be coordinated by the National Commission but shaped and led collectively by the sites themselves, ensuring sustainability through shared ownership.

Challenges and Successes

Challenges

- Conflict in collaboration: At first, attempts to avoid disagreement slowed progress. Accepting conflict as part of collaboration – and learning how to manage it – became essential.

- Stretching limited resources: With minimal funding for promotion, the team relied heavily on trust, co-design, and the advocacy of sites themselves. This required patience and strong relationship-building.

- Balancing top-down and bottom-up: Sites wanted autonomy, but the Commission had to provide structure. The gradual move toward devolved decision-making has required constant adjustment.

Successes

- Stronger network cohesion: For the first time, UK UNESCO sites across all designations began working to a shared agenda.

- Open innovation in heritage: Instead of site-by-site projects, resources and knowledge are now shared across the network, multiplying their impact.

- Digital reach: The co-created map and resource hub demonstrated the power of organic, cross-site promotion, bringing heritage to online audiences as well as physical ones.

- Collaborative enterprise: From shared films to joint private-sector partnerships, sites discovered opportunities they could never have achieved alone.

- International recognition: The model was so effective it was invited to Estonia, where the UK team supported the Estonian National Commission to replicate the process.

Discussion

The From Global to Local programme has shown that UNESCO sites are far more powerful when they act together than alone. Building networks takes time, trust, and the courage to share ownership – but the rewards are clear: stronger partnerships, wider public impact, and a more resilient future.

As the founding director of the Global Resilience Institute once said: “There is no point in being an island of resilience in a sea of fragility.” The UK’s UNESCO network has taken this to heart, recognising that by pooling knowledge, resources, and voices, local heritage can speak with global power.

Further Resources

Websites:

Images

Image Credit: Liam Smyth, Global to Local Programme Lead, UNESCO UK National Commission.